Safer Spaces and Social Identity Formation

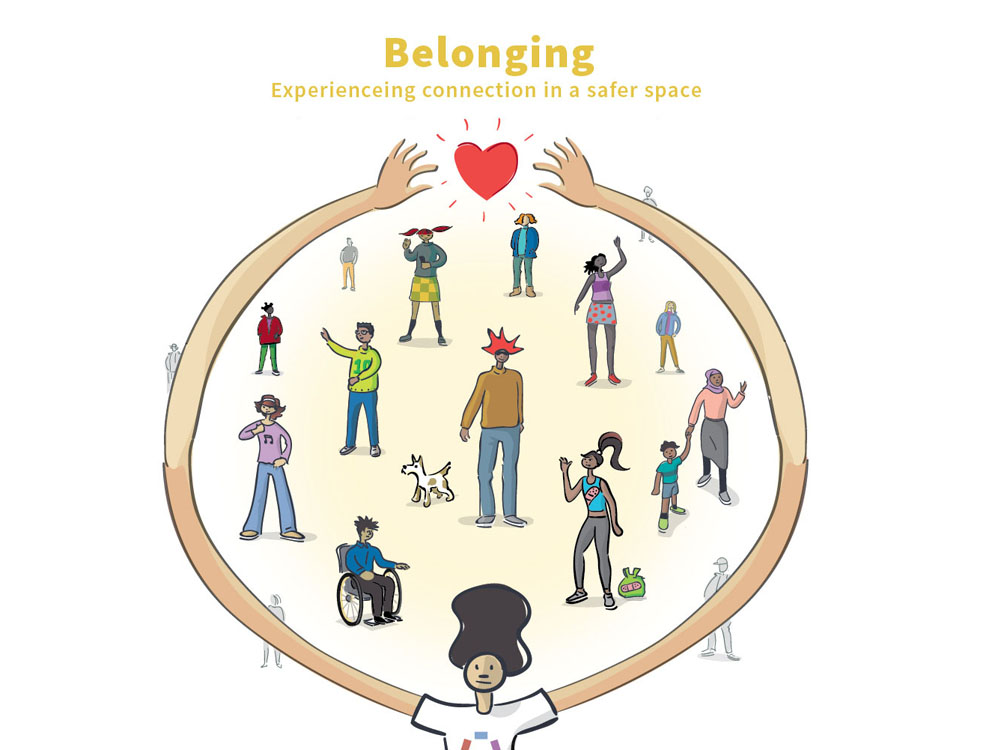

Our model describes creating positive safer spaces that respect differences, on-line and off-line. The program supports young people to explore diversity and define positive social identities for themselves, against many influences. Indications are that this protects from extremist influences and promotes positive engagement in community activities. This Safer Spaces Model captures key learning from The Students Commission’s Social Identity Formation project, in partnership with the RCMP, which was funded by the Canadian Safety and Security Program. Click through the panels to see it visually.

For more information view the full program model and step-by-step details

For the literature and environmental scan review, click Social Identity Literature Review

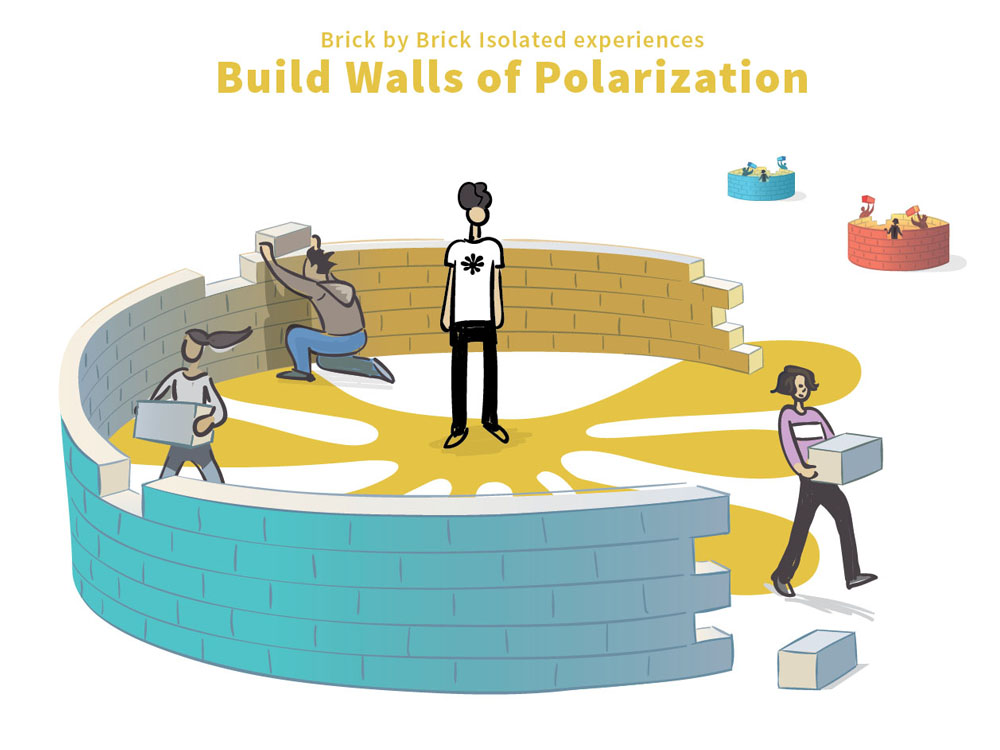

Social identity formation involves the development of “us” and “them” categorizations (Onorato & Turner, 2004) and sometimes, involves seeing yourself as an exemplar of some social category like an activist, rather than a unique person. One may feel personally anonymous and not responsible for actions you take to further your group’s goals (Hennigan & Spanovic, 2012).

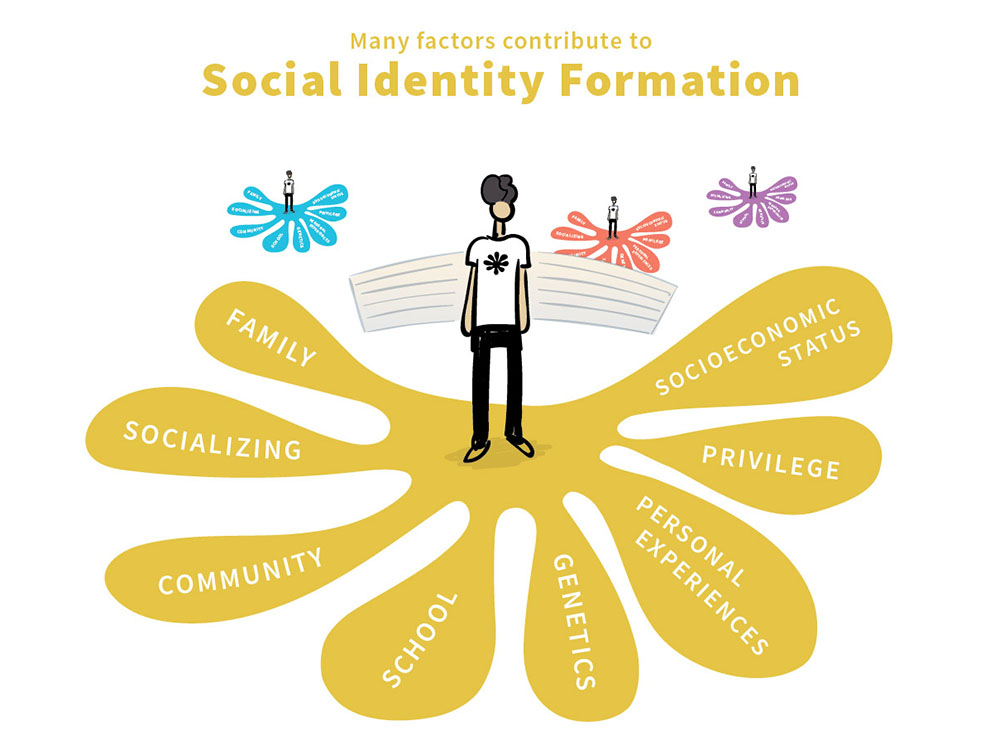

Social identity formation begins at a young age through a combination of genetic and environmental factors, such as family. Identity may create boundaries for feeling safe within. These factors play an important role in shaping one’s identity and how one is viewed and treated by others. The relationships and individuals who contribute to one’s environment are key to social identity formation.

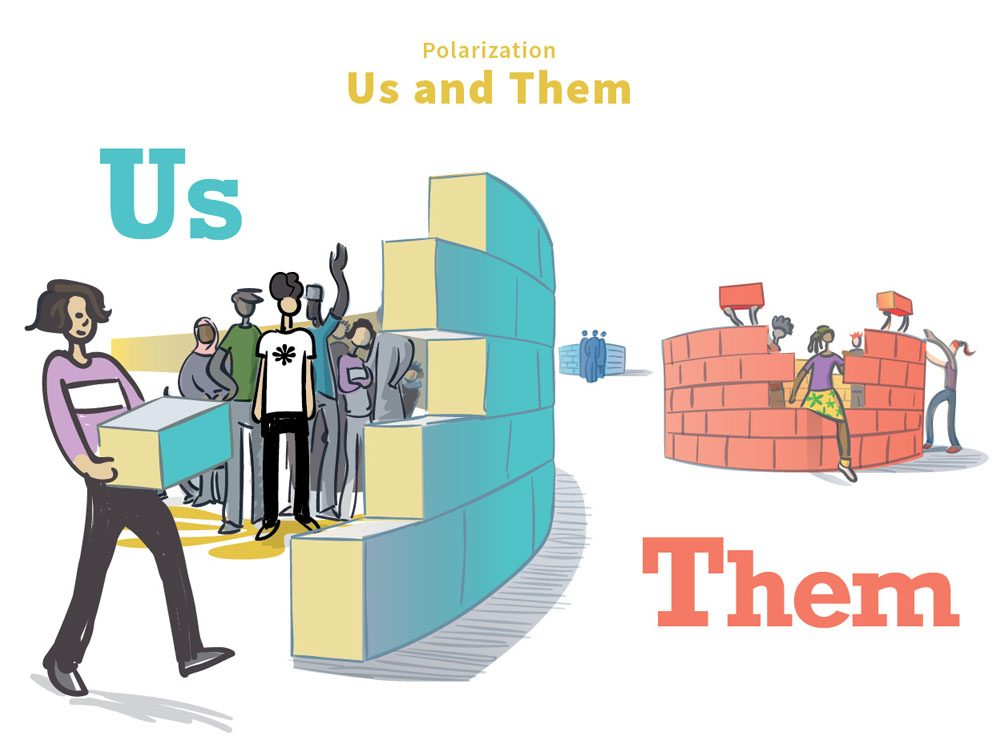

The sense of ‘Us’ described by a sense of community, comfort or closeness is made possible by having the spaces to build relational capacity. Cheering for the same home team, speaking the same language, and a sense of ‘insideness’ are examples of an ‘Us’ culture. ‘Us’ feels familiar, safe, and can even feel like home. ‘Us’ also exists within implicit or unspoken boundaries and or explicit ones.

Those beyond the familiar ‘Us’ are often perceived as ‘Them.’ They may be underestimated, feared, disliked or even hated. They are considered ‘Them’ for many reasons: different culture, political views, religious beliefs, race, gender, ability, sexual orientation etc. The distance between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ is known as polarization. The more homogenous or similar environment one comes from, the more different ‘Them’ likely will seem.

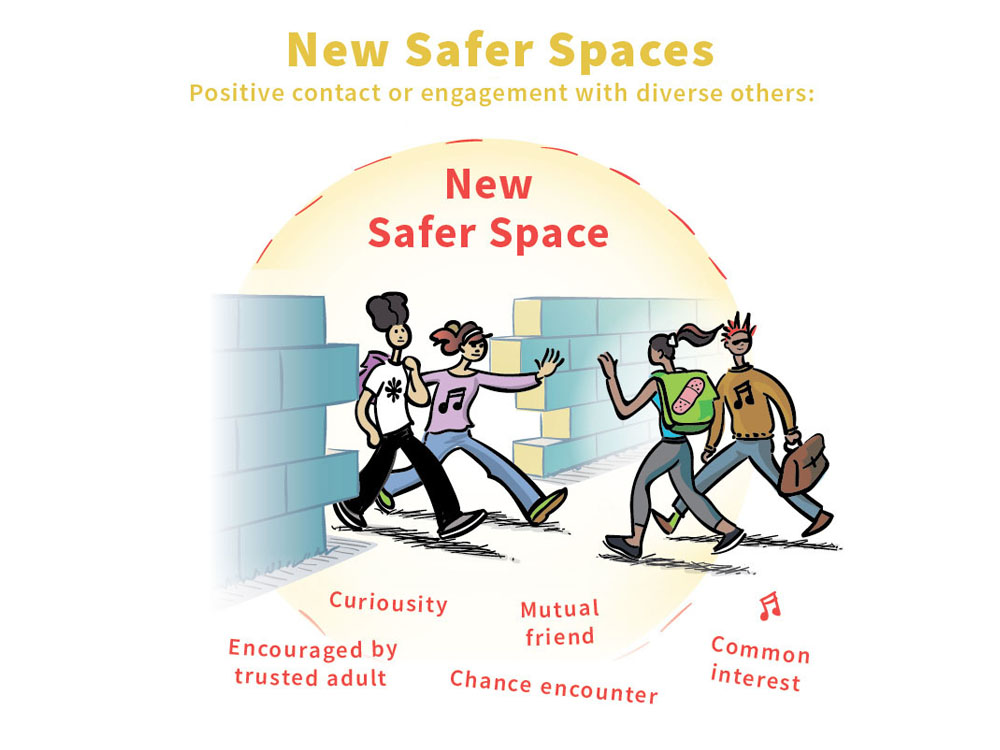

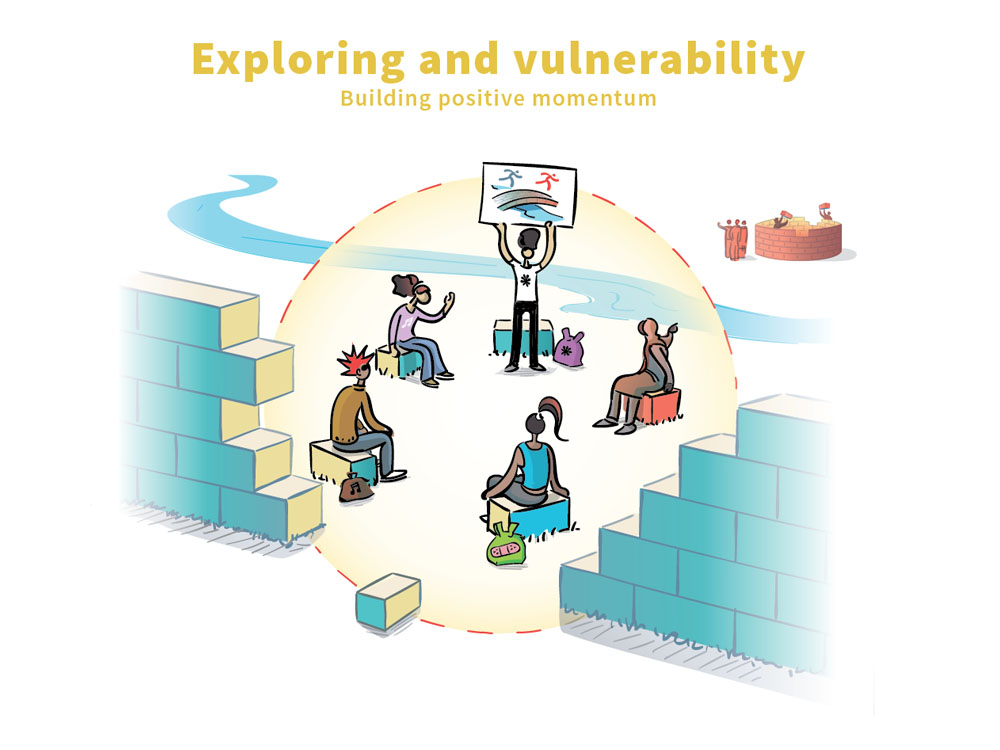

Within a safer space, one’s abilities, experiences and perspectives are respected, heard, explored, and celebrated. A safer space is crafted using a variety of safer space building factors. The comfort and security of the space depend upon the group membership. Dynamics can fluctuate with the addition/absence of members and the space may become compromised prompting someone to retreat and return to their previous notion of ‘Us.’

When a safer space remains intact, a group builds positive momentum towards meaningful connection and identity development. Through group interactions members develop trust and feel validated for their presence. People begin to realize they are not as different from one another as they might have initially thought. As group interaction embodies qualities of safety, the more confident members begin to share their stories.

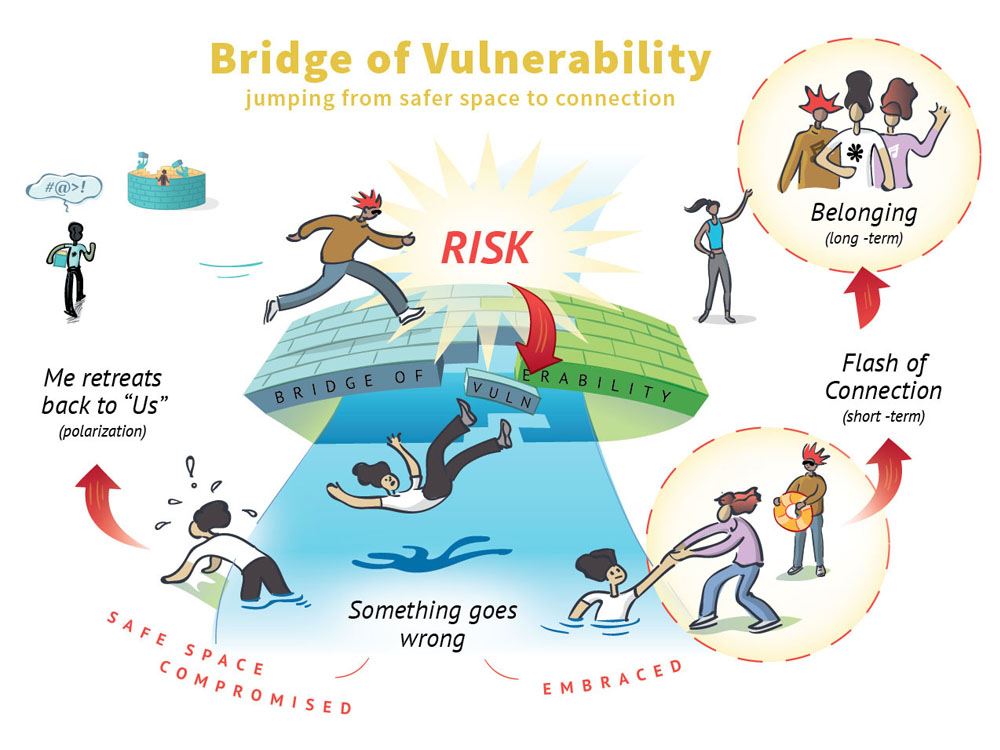

Moving on a bridge of vulnerability from safer space to connection, it is possible for something to go wrong when sharing stories. The vulnerable can feel shame, rejection, or self-hate. Different people in various types of minorities (shy, colonized, transgender), which are often not perceived by others, take greater risks in sharing their story. Hence, some will never be completely safe in these spaces, though may feel “safer.”

Group cohesion and one’s sense of closeness to each person in the group depends on the frequency of interactions, willingness to participate, and courage to be vulnerable. Taking time to debrief and recognize brave moments in the group can encourage more vulnerability. Connection with one another increases, the more often group members cross the bridge of vulnerability.

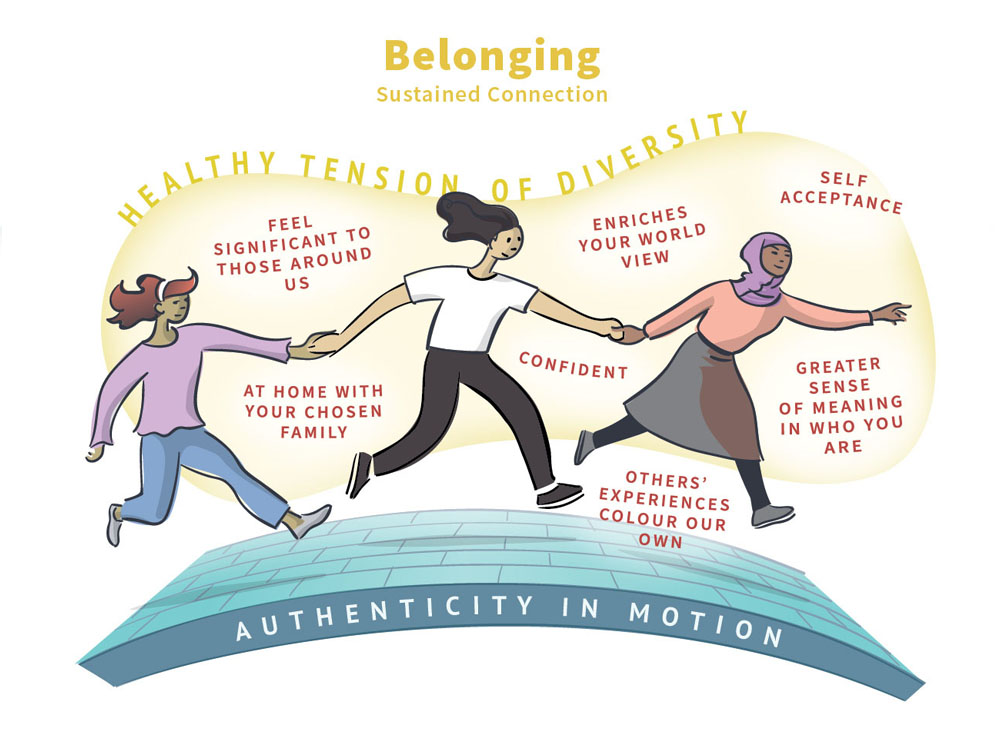

Repeating experiences of safer spaces builds capacity to create connections to diverse others, living in a series of well-connected safer spaces. One’s sense of belonging expands, including individuals from the original ‘Us’-family, friends, and communities to new and diverse ones. The phrase ‘chosen family’ resonates with many people when thinking about their sense of belonging.

Once people experience connection sparked by vulnerability and feeling grounded in their sense of belonging, they are prone to seek out rich safer spaces to hash out the deeper parts of their identity. People may be braver, explore more nuanced aspects of their identity and probe into deeper issues in future safer spaces, leading to more vulnerability, connection, and a wider sense of ‘we’.